Charlie Hebdo says “No more Muslims!” The French publication has declared a new war on Islam – the combative religion. The values of free speech and expression are touted by many news organizations, politicians and pundits around the world, but nowhere are those principles more on display than on the newsstands that carry the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo.

For more than two decades, the magazine has stood to humor and shock the senses of its readers. The left-leaning, anti-religious publication was less intended to be a paper of record or a pinnacle of journalism and more driven by a desire to make a political point that its writers and cartoonists thought were missing from the media landscape.

Those points were sometimes overshadowed by its prominently displayed editorial cartoons that would be deemed offensive by the sensitive moral standards of the western world.

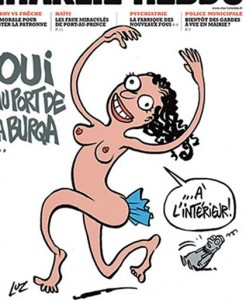

Figures in France’s boisterous political scene, Christianity, Judaism and popular culture were caricatured in a manner intended to embarrass and humiliate, a bold showing by the cartoonists that they were willing to push whatever line of decency had been attempted by outside influencers. But it was their depictions of Islam that drew the most attention and inflamed critics the world over.

In 2006, the magazine was criticized by several Islamic organizations after it re-published several cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammad that had been printed in a Danish newspaper two years earlier. The magazine added several cartoons of its own, including one in which the prophet confronted extremist supporters by saying, “It’s hard to be loved by jerks.” The issue sold more copies — 160,000 by some estimates — compared to a regular copy of the magazine.

One year later, three religious organizations sued the magazine, claiming in court that the cartoons were racist. Philippe Val, the publisher at the time, shot back saying, “It is racist to imagine that [the plaintiffs] can’t understand a joke.” The court agreed, acquitting the publisher and holding that the cartoons were in line with the country’s long-held tradition of satire.

Read more: Failed extortion, Swedish party girl fled America

The case inspired the magazine to continue pushing the boundaries. Its cartoons became more graphic, more bold and more offensive. In 2011, the paper announced it was changing its name to Charia Hebdo and appointing the prophet Muhammad as a guest writer. “100 lashes of the whip if you don’t die laughing,” Muhammad was depicted as writing in the issue.

Days after the issue hit newsstands, extremists firebombed the downtown Paris offices of the magazine. Officials speculated the attack was in response to the magazine’s history of caricaturing prominent Islamic figures brought to a head by the Charia Hebdo issue. If the attack was intended to strike fear into the hearts of the writers and cartoonists on staff, it had the opposite effect — publisher Stéphane Charbonnier told reporters that the attack was likely carried out by “idiots who betray their own religion.”

In 2012, the magazine doubled-down on offense following the controversial release of an anti-Islam film called “Innocence of Muslims.” The film, which circulated on YouTube, prompted angry anti-American demonstrations throughout the Muslim world. In response, Charlie Hebdo published several cartoons depicting a nude prophet Muhammad. Riot police surrounded the magazine’s offices for days out of fear of a retaliatory attack that never came.

Several French politicians criticized the magazine for inflaming tensions with their cartoons, with foreign minister Laurent Fabius questioning whether it was “sensible or intelligent” to print them. Again the magazine pushed back, with Charbonnier questioning: “We do caricatures of everyone … and when we do it with the [prophet Muhammad], it’s called provocation?”

On Wednesday, the paper published a cartoon on Twitter that lampooned the Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The terrorist leader is shown wishing his supporters well for the upcoming new year. One hour later, the paper was thrust into the international spotlight after two masked men stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo, fatally shooting 12 people and injuring 10 others. Five cartoonists, including Charbonnier, were among the dead in the attack.

Read more: Ambulance chaser lawyers sued Red Bull, Claiming not growing ‘wings’

After killing a police officer at point-blank range outside the magazine’s offices, one attacker was captured on video saying in French: “We have avenged the prophet Muhammad, we killed Charlie Hebdo.”

World leaders — some of whom have been critical of the magazine in the past — have expressed only support for the publication in the hours following the attack. Heads of government in France, Canada, Germany, Russia and the United States have all denounced the incident as an attack on free expression and an act of barbaric terrorism.

As noted by The New Yorker’s Amy Davidson, France will have a challenging time deciding how best to respond to the attack in the days and weeks to come. Countries have, historically, not made the best decisions following a large-scale act of terrorism — the knee-jerk reaction would be to impose a sort of self-censorship so as not to encourage similar attacks on other institutions — but history has also shown that’s not what Charlie Hebdo would have done.

Matthew Keys is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.

One Comment

Leave a Reply