Does This Burqa Make My Butt Look Fat?

When female Syrian refugees, in the intense desert heat, are spending their dwindling food vouchers on girdles that advertise they’ll sweat the inches off their tummies, you know the desire to be skinny has gone too far. This is an international body image crisis. As silly as that sounds, those girdles demonstrate how warped the world has become with the quest to look skinny. Besides, a little blubber could keep a refugee alive when the next epidemic of dysentery splatters the camp.

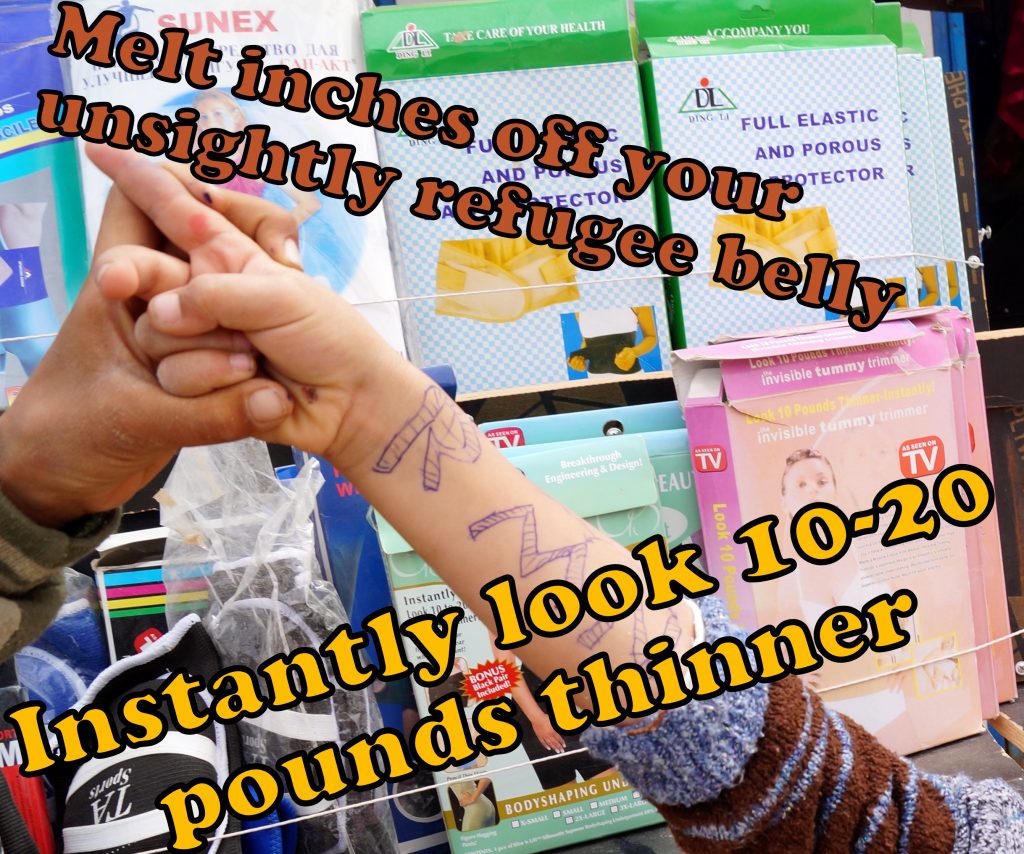

I was recently going through the photos I took while at Za’atari, which is located in Jordan near the Syrian border and is the largest Syrian refugee camp. At the time of taking the image of the boy with writing on his arm, I didn’t notice that the stall behind him was selling girdles to nutritionally deprived women. In English writing, across the packages, are the words “as seen on TV.”

Globally, our body images are affected by “as seen on TV” whether we admit it or not. I’ve often thought, “This is the year my ribs will protrude like Keira Knightley’s.” OK, that’s not going to happily happen, because mine won’t look like hers unless I’m dying. Pathetically, death-camp-skinny for female leads is still desirable over healthy or, God forbid, chubby.

A friend of mine who’s worked for 30 years in the film industry told me about casting decisions for female roles being based upon thigh gap. Talented, beautiful women were rejected because the people doing the hiring wanted skeletal crotch above all else. Actresses’ starvation halitosis bowls my friend over on set. But we expect to hear this regarding the film and television industry. What blows my mind is when I see body image spill into my industry, writing. I mean, who cares what a writer looks like? You rarely see us. But people care — and not just the publishing house marketing department.

Repeatedly on social networking, I witness women travel writers being praised for their physical appearance and not their work. An American author posts a photo of herself beside a sign in France that’s announcing her new book. All the author’s friends post praise about her physical beauty and none congratulate her on her achievement. I rarely see any mention of physicality regarding my male writer friends. I’ve never seen, “Still looking great, Gary Buslik,” or “So pretty, James Dorsey.” The guys get compliments on their writing, their wit, the importance of their stories.

I felt the salt rubbed into my porky belly up close and personal last week. I grew up in a family that is perversely obsessed with weight loss, even among the skinniest members. This diseased thinking is passed on from one generation to the next through behavior and comments — like the time I lost 10 pounds (going from 118 pounds to 108) and my slim mom chirped, “Oooh, I got my daughter back.”

Last week I was tagged in a photo on Facebook. A writer (let’s call her Bliss) from the anthology I’ve just edited had taken me out for lunch. She posted a photo of us online. Bliss announced in the caption (visible on both our Facebook walls) that I was her editor. Then the praise for her looks started from her friends. She’s tall, thin, gorgeous and weight-conscious, but not one of her social-networking acquaintances asked what she’d written or what work of hers I’d edited. All her friends told her how beautiful she was instead.

Bliss wasn’t fishing for compliments about her appearance. At first, I wanted to find ways to talk about her terrific essay, her misadventure in Africa and the book. But then I started to feel fatter with every “beautiful” that was lobbed at Bliss. I wanted to cry out, “Hello, there are two women in this photo! I’m the one with double chin whose eyes are darting around maniacally!” Finally one of my friends, a tech writer and former book-show host, asked if Bliss was one of the writers in “Wake Up and Smell the Shit.” And then, thankfully, another one of my friends rescued me by saying that I look psychotic in the photo. Phew. Because psycho is better than fat, for sure.

I can’t think of anything I’ve ever encountered before that depicts how out-of-control the pressure to be skinny is as girdles for sale in a refugee camp. But it’s understandable why the Syrian women feel like fatties even while on rations. The West is exporting unhealthy body image. But it’s not just because of “as seen on TV.” We do this to each other, like Bliss’ friends innocently putting focus on her looks instead of her work.

And while on the surface, fat shaming and ugly bashing seem worse, this more-subtle focus on good looks devalues a person’s real worth. And we can all help stop this by being more creative when we compliment someone. Instead of praising a woman on how beautiful she looks as she accepts her Nobel Peace Prize or gets her grade 12 diploma, how about congratulating her on her accomplishment?

READ MORE: KIRSTEN KOZA GOES INSIDE ZA’ATARI SYRIAN REFUGEE CAMP FOR THE BLOT: PART 1 – IMPRISONED BY HOPE

Read more: Part 2: LIES AND ILLNESS: INSIDE AL ZA’ATARI SYRIAN REFUGEE CAMP

Read more:

________

Kirsten Koza is the author of “Lost in Moscow: A Brat in the USSR,” a humorist, adventurer, journalist and contributor for TheBlot Magazine.