Activist Jennifer Finney Boylan is the author of 13 books, including “She’s Not There: A Life in Two Genders.” A novelist, memoirist and short-story writer, Boylan is also a nationally known advocate for civil rights. She serves as the national co-chair of the board of directors of GLAAD, the media advocacy group for LGBT people worldwide.

Boylan was recently given the great honor of being presented with the 2015 Wesleyan University Distinguished Alumna award, 35 years after graduating as a man.

My wife and I met at Wesleyan, and we were married as man and wife for 12 years; now we’ve been married as wife and wife for 15. I was editor-in-chief of the Wesleyan newspaper, on the radio station’s board of directors and in a comedy group. I was the kind of person who made a big noise.

But back then, there was no model for coming out as transgender. I remember going to the library to find people like me, and finding either nothing or books that were full of ridiculous psychoanalytic theories that some idiot had clearly just made up. There was no transgender person around to tell them, “That’s all complete bullshit.”

For many years, that remained the case. In fact, that’s still the case. There’s this guy, J. Michael Bailey, who is still coming up with crazy theories on transgender people, and some members of the psychological community still pay attention to him even though his findings appear to be based on nothing other than whim.

In some ways, I had a hard time at Wesleyan because I had a big secret and no language for talking about it. On the other hand, to only look at those years from the lens of the transgender woman I became years later would do a disservice to who I was then.

Mostly what I remember about being an undergraduate was being encouraged to have an imagination. My writing professor was Franklin D. Reeve — actor Christopher Reeve’s father. He really saw something in me. I went into Wesleyan as a frightened, confused person not sure of what I was going to do with myself, and I left as a person who had gained confidence in my ability to write. I thought then that my writing would help me in years to come. It gave me a sense of identity and purpose, but I thought if I used my writing skills cleverly enough I could make it OK for me to stay a boy.

It turned out that it wasn’t possible for me to stay a boy, but Wesleyan gave me the skills to survive in the world as someone who was going to reveal a complex and unsettling secret and survive the transition.

Nothing taught me how to live in the world as a woman more than my work as a writer. When you come out as trans, at least when I did, I felt it necessary to send lots of letters and explain myself to people. It seemed like nobody knew what being trans was, and I felt I had to provide a narrative so people could understand. One of the places where I posted a rather lengthy note was in the Wesleyan class notes. A classmate joked later, “When is the award for best class notes ever?”

Read more: Transgender Author/Activist Jennifer Finney Boylan Continues to Open Minds

By my 25th reunion at Wesleyan, there were a lot of people who wanted to grill me about it. It wasn’t that they were hostile; it was that they wanted a debriefing. I obliged them, although I have to say there’s something undignified in having to participate in a conversation in which your identity is a matter of debate and that you could have a conversation about your humanity where you could technically win or lose. Other people don’t have to do that. On the other hand, I’m a conflict-averse person, and I think that fundamentally I want to win people over. I’m wired that way. So I took part in all of those conversations — even as degrading as some of them were.

Then, 10 years later, at this recent 35th reunion, I wasn’t put into the position where I had to explain. One of the things about getting older is that people accept the fact that shit happens. Lives change. The fact that I came out as trans is still a less-common experience, but you look around at the group of 56- and 57-year-old people, and they’re not the youngsters you knew back in the seventies. They’ve had children, gotten married and divorced, people whom we have loved are dead, and there have been all sorts of terrible and wonderful things that have come to pass in everyone’s lives. One person changing genders may no longer seem — to most of my friends — as the most significant of the changes any of us have been through.

When I first announced it in the newsletter, it was 2001, and a number of people were perplexed. Transgender issues have evolved so significantly in the past 15 years, and I would say there are a lot of forces making that possible. I hope, I can humbly say, that my own writing is not a completely insignificant part of the change in the national conversation around the issues.

Many people who learned from the class notes probably thought, “Really? Seriously?” or “Whatever.” But it’s one thing to read about it and to be explained the issues, but it’s another thing when you encounter the person. There’s something about showing rather than telling that wins people over. No, wait, winning people over is the wrong phrase. But there’s something about being with the person who has transitioned that makes the light go on in a way that lecturing people and explaining, sort of self-righteously about your suffering and your private misery — doesn’t. The lectures I gave didn’t win many people over. I think I annoyed a lot of people that way.

The reaction to my coming out was not usually what I would have liked: “Oh, we’re so sorry for what you’ve gone through. Welcome to womanhood.” I got a few of those, but a lot of the reactions I got were, “What are you talking about? Are you serious? Have you thought about this?”

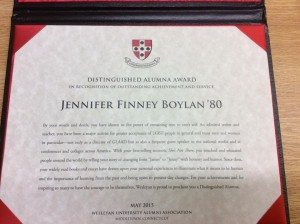

If I am seen as a transgender specimen, it is a role that I’ve consciously chosen, and no one is to blame for it but me. At this 35th reunion, the college named me among its “Distinguished Alumna” which is a big deal. There was a very formal ceremony and the president gave me this thing that looks like a diploma. The language on it is quite moving. I took a picture of it and posted it on Facebook.

“By your words and deeds, you have shown us the power of remaining true to one’s self. An admired writer and teacher, you have been a major activist for greater acceptance of LGBT people in general and trans men and women in particular — not only as a director of GLAAD but as also a frequent guest speaker in the national media and at conferences and colleges across America. With your best-selling memoir, “She’s Not There,” you touched and educated people around the world by telling your story of changing from “James” to “Jenny” with honesty and humor. Since then, your widely read books and essays have drawn upon your personal experiences to illuminate what it means to be human and the importance of learning from the past and being open to the present-day changes. For your achievements and for inspiring so many to have the courage to be themselves, Wesleyan is proud to proclaim you a Distinguished Alumna.”

The reason I mention all of this is that they gave it to me and celebrated the work I’ve done. It’s true that I’ve been singled out as this transgender spokesmodel and, yeah, there are times when I kind of wish I’d kept my mouth shut. It certainly wasn’t the thing I thought I’d be known for when I graduated. But, now if there’s some transgender person or the loved one of a transgender person who goes to the library at Wesleyan looking for information on the lives of trans people, they’ll find books written by me, and they’ll find books written by transgender author Janet Mock and all sorts of other people.

The takeaway is that people, like the younger version of me, can go to the library and know that they are not alone, and they’re going to be OK. That’s really good work to have done. So, if I’m a specimen that may be true, but if you can look back at the work you’ve done in your life and say, “Something I did made life better for other people,” that’s kind of a nice gig, right?

Dorri Olds is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.