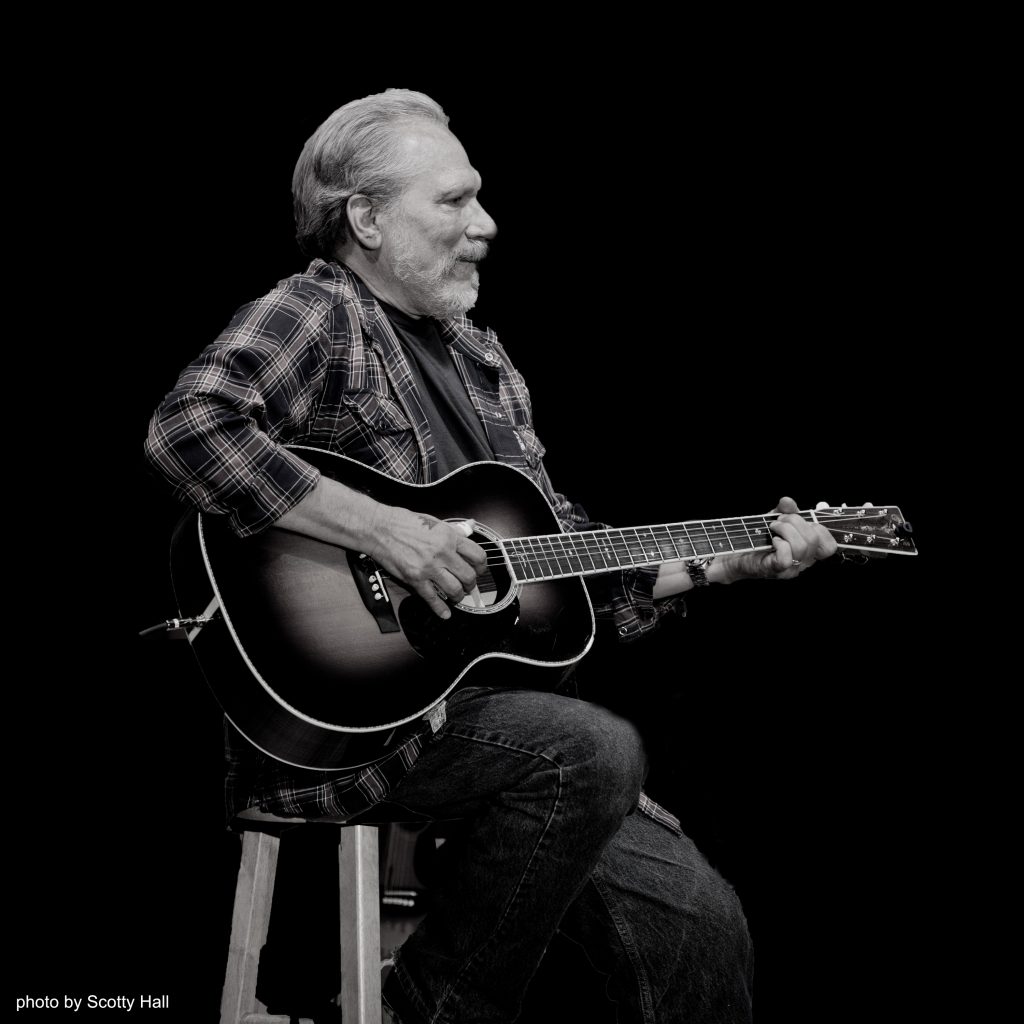

Guitarist Jorma Kaukonen established his living-legend status in the late 1960s with the San Francisco psychedelic band Jefferson Airplane, his guitar work a highlight of hits like “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love.” (In this author’s opinion, Kaukonen’s shimmering piece “Embryonic Journey” from the Airplane album “Surrealistic Pillow” is a perfect display of his prowess.)

By the early 1970s, Kaukonen and his longtime friend, Airplane bassist Jack Casady, had left the Airplane and acid rock behind to form blues-rock band Hot Tuna. In 1974, Kaukonen, released his first solo album, “Quah.” Since then, he has enjoyed a prolific career, both with Hot Tuna and as a soloist. Kaukonen also teaches guitar at his Ohio ranch, Fur Peace, where guest instructors include blues guitarist Rory Block and G.E. Smith, former axeman for the “Saturday Night Live” house band.

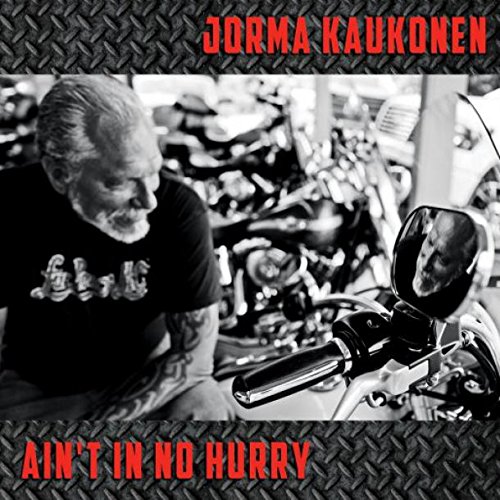

This year, Kaukonen celebrates the release of his latest solo album, “Ain’t In No Hurry,” which came out in February on Red House Records. Fans of San Francisco psychedelia a la Airplane will be surprised by the album’s homespun charm. Highlights include “Suffer the Little Children to Come Unto Me,” based on a rediscovered Woody Guthrie poem. TheBlot Magazine had the privilege of interviewing this journeyman musician about his long, fruitful career as a musician and a teacher.

Robin Cook: There are some traditional songs like “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” on “Ain’t In No Hurry.” Is it challenging to put your personal imprint on those songs?

Jorma Kaukonen: For me, there’s really not a challenge because even when I was a kid, the way that I approached learning tunes, I learned what was necessary so they sounded like tunes are supposed to sound like. But I never tried to replicate somebody else’s performance. Just by my inability to mimic people allowed me to put my own imprint on them. And I’m comfortable with that.

One of the songs is a Woody Guthrie lyric you put to music. Could you tell me about that?

We’re friends with Nora Guthrie. She’s Woody daughter, and she’s protector of the Guthrie legacy. Over the years, both Larry Campbell — he and I co-wrote the music — we talked to Nora, and she said, “Woody has all these poems. And we’d like to do some music some time.” And we never really followed up on it. But when I was doing this [album], I realized this is the perfect opportunity. So I e-mailed Nora, and I asked her, ’cause they have thousands of poems that Woody wrote. People keep going, “Wow! You found some lost Woody Guthrie stuff!” I’m sure there is lost Woody Guthrie stuff, but Nora and the gang, they have a lot of stuff that’s not lost. Nobody’s ever seen it.

So I said, “You know, I’m a bluesy kind of guy. Send me something you think I’d like.” So they sent me four poems, and they sent me actual photographs of the actual sheets of paper he wrote them on. It was so cool. And three of those four poems were really like beat poetry. And I couldn’t see a way to put the kind of music that I would write to them. But the fourth one, “Suffer the Little Children,” I wrote with Larry, then I went, “Wow, that’s great.”

Was some of the older material on the album stuff you’d been wanting to record for a long time?

“Brother Can You Spare a Dime,” that’s a song I got turned on to when I was a kid. My mom loved the song. I heard the Bing Crosby version, I heard some other versions, a lot of people have done the song. About two years ago, my friend Barry Mitterhoff, who plays violin with me a lot of time, and I got together, and we started working out an arrangement of the song. I finished the arrangement, and I practiced it for a year and half before I recorded it because I really wanted it to be right.

You think about it, the lyrics of that song were written by Yip Harburg, and he wrote the lyrics to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow, so if you want to think about it as a metaphor, “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” is the beginning of the Depression, and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” the end.

You, of course, played with some of the great rock ‘n’ roll singers. Were you nervous about stepping out and singing yourself?

Absolutely. Before I got into rock ‘n’ roll bands, I was a solo artist. I immediately found myself playing with some of the great voices of my time. As a younger guy, I got to back Janis Joplin a little bit. Obviously, [Jefferson Airplane] had Signe Anderson and Grace Slick, one of the great rock voices of my time, and Marty Balin. When the time came for me to step out on my own, I found myself very self-conscious about my voice.

So my friend David Crosby — I remember agonizing about this years and years and years ago — went, “Look, Jorma, most of the kinds of music that guys like we do, it’s not operatic, it’s not musically gymnastic. We need to be able to sing in pitch. That’s important. We need to be able to sing in tune. But other than that, we’re just telling a story. So you need to have character to your voice.” That was a big help to my psyche at the time.

What are your memories of Janis?

The Janis that I knew well was like 1962 to when she got in Big Brother [and the Holding Company]. In those years, she was a folky, bluesy Janis. She did so much more than channel Bessie Smith, but that’s kind of like what she was going for at the time. And it as such an honor to play with someone who was that good. That’s the year that I knew her, that we knew each other as friends. After that, everyone was so busy with their career, they didn’t hang out much. But she was just such a committed artist. A lot of times, people talk about artists like Janis, they tend to focus on some of her self-destructive idiosyncrasies. And we all had some of those. But to get totally by that, she was a great artist, and it was a great honor to have played with her.

What keeps your musical partnership with Jack Casady going? You’ve played together since you were teenagers, right?

Ha! Yeah, we sure have! We started playing together in ’58. If we were doing a joint interview today, and Jack and I were talking to you, first of all, I wouldn’t have to talk much. When he gets into interviews, he likes to do the talking, but you would find us to be very different people. However, as friends, as my oldest friend, as friends we’ve always cut each other a lot of slack, never had an argument. We don’t agree about everything; we’re both opinionated, but we’ve never argued about anything. We’ve never had a band meeting. We’ve always respected each other as people and as musicians, and when we play together, whatever it is, there’s some kind of undefinable chemistry that’s there, and we listen to each other, and it always seems to work.

Could you give me some history about your Fur Peace music camp?

Sure. I bought 126 acres in southeast Ohio in 1989, and we built the Fur Peace Ranch. We just had a session this weekend. Our sessions are Friday morning to Monday morning. We have an NPR radio show, we have a little restaurant, we have a theater, and we have our workshops and cabins. Our idea was to make the learning process of the music that me and my friends that teach with us utterly untimidating and accessible to the students, and I think we’ve been successful at that.

Had you thought about becoming a teacher before building the ranch?

When I moved to California in 1962, I was already beginning to play out, but there were really no jobs. And Paul Kantner, the rhythm guitar player of Jefferson Airplane, of all people, had been teaching banjo at this little music store in San Jose. He said, “You ever teach guitar? You could make some money.” I went, “I’ve never thought about that before,” but I gave it a shot, and I really liked it. So when I started teaching guitar full time in 1962, obviously during the Airplane years, I wasn’t doing it, but in the ’80s, I taught some classes at the New School [in New York], I started to get back into it again … and that set the scene for the Fur Peace Ranch experience.

Do you find it’s sort of a learning experience for you to teach other people about guitar?

Absolutely, absolutely. I think teaching cannot help but make the teacher a better player. For one thing, you have to slow down and stop what you’re doing and explain it in a way that somebody else can actually [understand]. And doing it slowly gives you a chance to examine what you’re doing yourself, and I’m always coming up with ideas. I love to teach.

Robin Cook is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.