“Syrians can make something from nothing.” Uh, not really. (Part 2)

“No pictures!” I have to agree to this before I’m allowed inside the gate to Jordanian Aid Hospital (a compound of sheds) at Za’atari, the largest of the Syrian refugee camps, now the fourth largest city in Jordan. Once through the gate I’m immediately squished by a teeming throng of coughing, desperate-looking refugees waiting for treatment. This is congested beyond the ERs I’ve visited on the busiest holiday weekends in Canada and England. I hold my breath and try not to touch anyone or anything.

Manal Salem al Ahmad, a Syrian refugee and mother of four, who is guiding me through the camp, pushes into an administrative office. I’m instructed to sit at a table with a group of men wearing UNHCR (the U.N.’s refugee agency) insignia. After visiting a school (see Part 1) and being told that the schools need “everything” in the way of donations and that UNICEF is the best organization for making donations to, I decide to get right to the point and ask, “What is needed most at the hospital?”

“Nothing.” The U.N. administrator stares at me blankly.

I’m incredulous. “The hospital doesn’t need anything at all in the way of donations, supplies? More doctors, nurses?”

“Nothing. The hospital doesn’t need anything.”

I might as well shred the list of questions I have for them. I’d actually believed I could make a difference if I informed the West of the best organizations to make donations to straight from the people working in a hospital. All the men at the table are staring coldly at me. I’m being lied to but can’t understand why. “What is the number one health ailment you are dealing with right now at the camp?

“Respiratory illness.” This is the truth, but that’s all I get from these men. Both Manal and the Jordanian teachers have already told me about respiratory illness. They’re all suffering. The camp is a permanent dust trap. I’m already coughing from the suffocating desert dust. Living here is a future diagnosis of emphysema. It is particularly dangerous for children and the elderly as it sets them up for cardiopulmonary disease. Then there’s the contaminated water that the teachers and Manal also told me about.

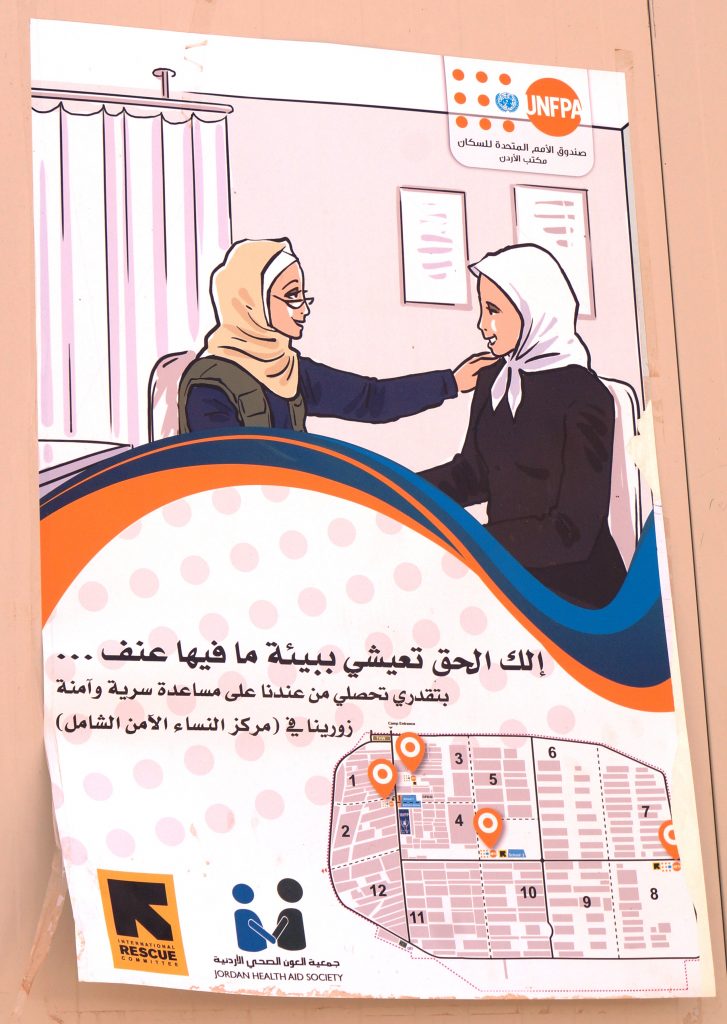

The water being delivered isn’t fit for drinking. The communal toilets are appalling. The close quartered conditions mean disease spreads fast. Mysterious fevers, STDs and violence run rampant. Right now Manal’s husband is at home, as there are no locks on the doors and someone always has to be there. Living in the camp is a daily health risk.

I go back to asking the hospital administrators about what is needed, perhaps specific medicines.

“Nothing. We have enough medicine.” The man looks hard into my eyes. I get up. I’m done here. “You can’t take any pictures at the hospital.” He threatens me with his tone. The others concur. I suppose if I took photographs they would show that everything is needed at the hospital, not nothing.

Manal is surprised that I am leaving so shortly. “You don’t have any more questions for them?” she asks me.

“No, they’re lying to me.” I say loudly so the UNHCR can hear as I depart.

“I know they’re lying!” Manal is pushing her way back through the masses of sick Syrians. “I had to go to the hospital recently and they had no medicine. There was NO medicine for us.”

“Why would they lie?” I ask her.

“I don’t know.” She’s as baffled as I am.

I wonder if their lies are due to pride. Perhaps the Jordanian hosts don’t want to admit to the world that living in Za’atari is utter hell because I can’t imagine administrators at hospitals in North America (even at the wealthiest hospitals) not producing instant lists of what is needed: another MRI machine, more staff, a new wing, a dedicated pediatric clinic.

Different stories coming from refugees vs. UN officials are not uncommon. On April 5 a demonstration of hundreds to thousands (depending on U.N. report vs. eyewitness report) of refugees turned violent at the camp. Refugees threw stones at a police post and tents and caravans were burned. The police returned fire with guns and tear gas, killing and wounding refugees.

Refugees claim that the demonstration was because a policeman ran over a child. The U.N. claims it was because they’d caught refugees trying to escape. An Associated Press report states that a driver tried to smuggle a Syrian refugee family out of the camp. Before I had official permission to enter the camp, a Syrian driver offered to put me in a burqa and smuggle me into the camp. It was the “getting out” that worried me.

Escape from the camp occurs daily and new refugees arrive as well. The word “escape” is almost misleading. This isn’t a case of “Hogan’s Heroes” escape attempts. There’s no wall surrounding this camp; fences are used to separate the refugees from food and registration buildings and there are also fences at the main entry gates. Refugees are allowed to exit but are supposed to return. The gigantic camp is mostly surrounded by open desert, but there is also the nearby small preexisting Jordanian village of Za’atari.

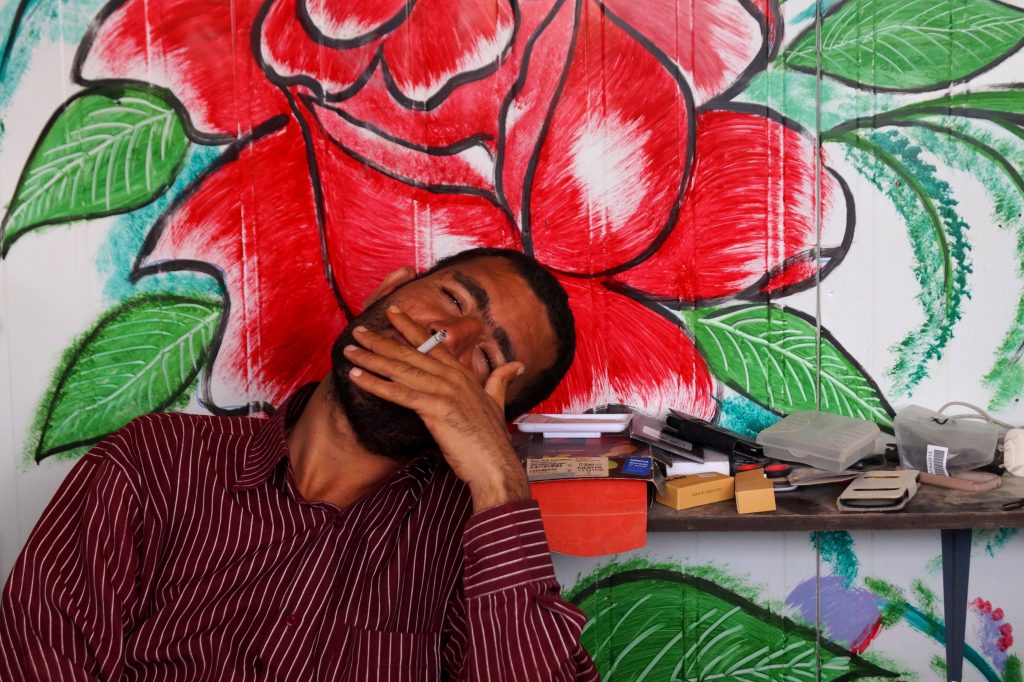

Similar to the Jordanian officials saying that the hospital needs nothing, there is also a dangerous belief that “Syrians can make something from nothing.” Murad Arslan (Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities) tells me that if Jordanians were in the same situation as the Syrians, they’d starve, where the Syrian people are so much more industrious and creative. Even my Syrian guide, Manal, proudly says, “Syrians can make something from nothing.” But the problem is that given nothing, they’ve been forced to make something by selling their tents and caravans, which were provided by relief funds outside the camp. Bedouins buy up the refugee tents because they love that they’re compartmentalized, and migrants working farm fields buy them as well. Refugees also break apart their caravans to build furniture to sell at the camp. Very little is provided to them.

However, what little that is provided is causing bitterness within the Jordanian population as well. It’s a small country and this isn’t the first massive influx of refugees. Anoud Abdelkarim Malahmeh (Jordan) wrote on my public (Writers’ Expeditions) Facebook wall, “All Syrian refugees take coupons … even the poor can buy whatever they want, even the most expensive food while poor Jordanians can’t afford bread sometimes.” She also said that Syrians were taking jobs from Jordanians and points out that Jordan is a poor country without oil. This sentiment is strongly felt in Jordan, but most Jordanians have also never seen inside a camp.

Resentment towards immigrants is a global issue. One time when I was at an East London pub, an out-of-work builder complained to me and my friend Sarah that we foreigners were taking all their jobs. My friend turned to him and said, “So you can dance the can-can can you — because I’m a can-can dancer.”

Murad Arslan says that the Syrians are largely taking jobs that Jordanians wouldn’t deem to do anyway. I’ve encountered these Syrians all across Jordan, such as bathroom attendants handing out toilet paper and wiping up excrement for tips and no wage. There are also Syrian adults and children at Roman ruins such as Jerash, trying to sell anything they can to tourists, even soiled and badly photocopied pages from guide books.

Child labor exists in the camp as well. Many children don’t attend school because they have to work to help support their families.

Jordan isn’t bearing the cost of refugees entirely alone as donations are coming from the international community (but not enough). It costs about half a million a day to run a camp like Za’atari and that’s just one camp. Where the West is failing inexcusably is when it comes to opening our doors to refugees. The U.S. took in a mere 31 Syrian refugees last year (though is speeding up the lengthy processing time). Canada said last year that they’d take in 1,300 refugees, yet as of last month they’d taken just 10. Wow, way to go Canada; at least the sign at the front of Za’atari in Jordan says “Welcome to Za’atari.”

Part 3 of “Inside Za’atari,” “The Not-So-Great Escape,” will detail the lives of Syrians in Jordan living outside the camps and how an NGO helps a Syrian woman set up a sewing business even though helping Syrians to start businesses is forbidden.

Kirsten Koza, the author of “Lost in Moscow,” is a Canadian adventurer and humorist.

6 Comments

Leave a Reply