“Rich kids don’t go into boxing. Boxing is a way out of the ghetto.”

That’s a quote from the sports documentary “Champs,” and it makes for a good synopsis of the movie. It’s a sad irony to study these men who were raised with violence only to escape through violence.

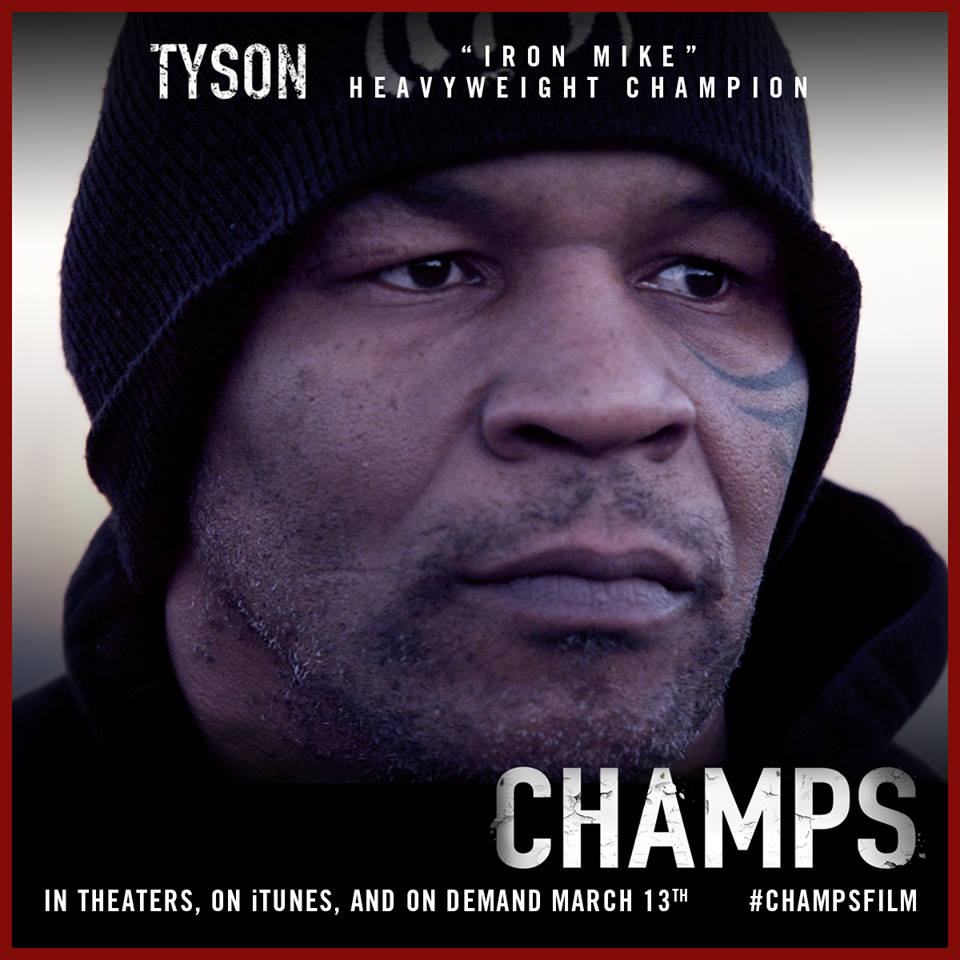

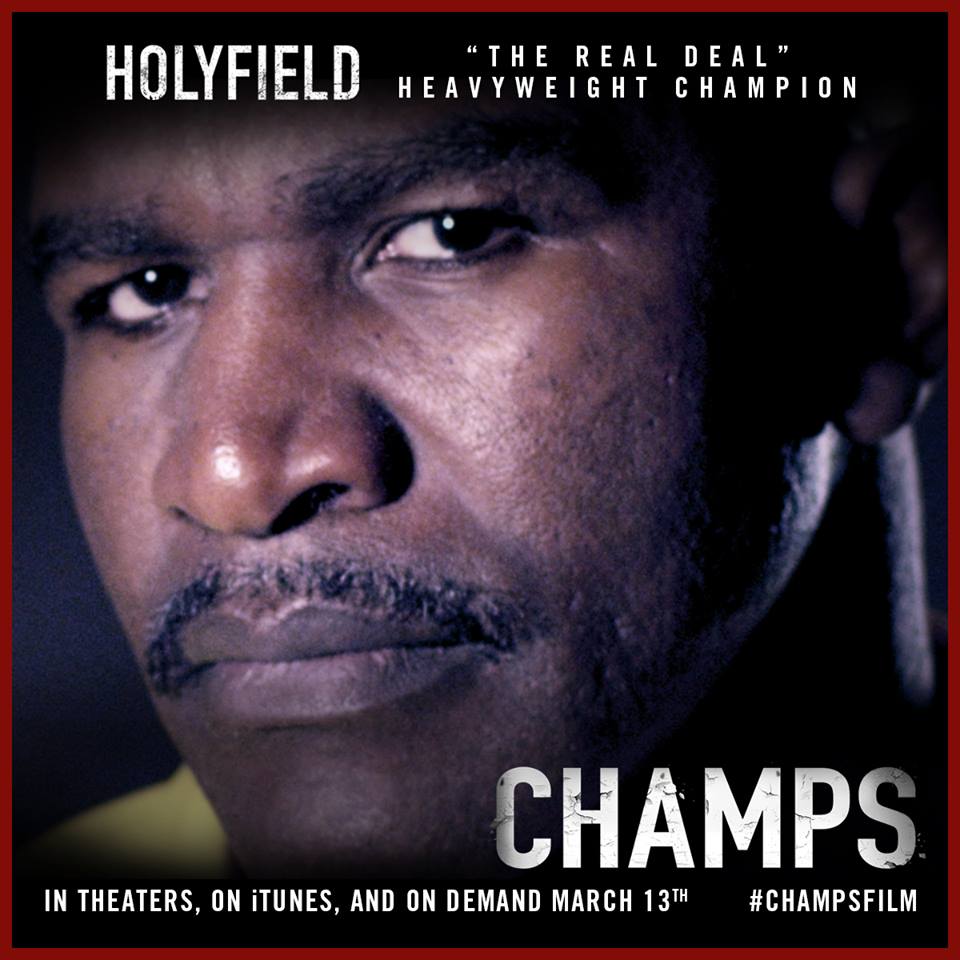

Heavyweight champions Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield and Bernard Hopkins tell their haunting tales, in between archival clips, reenactments and interspersed celebrity talking heads that include Ron Howard, Spike Lee, Denzel Washington, Mark Wahlberg, Mary J. Blige and 50 Cent.

“Iron Mike” (Tyson) is, by far, the most interesting. He seems laid bare, vulnerable, honest and sheds tears that seem genuine.

“The worst characteristics you can think of from black life is where I stem from,” Tyson said, referring to his ghetto neighborhood. “A lot of drugs, tons of violence. My parents were women who did sex on the streets. We weren’t safe in the house. We were always vulnerable. A lot of men [that slept] with my sister beat me.”

This is also the man sent to prison for six years for raping Desiree Washington. He only served three years. We hear him still claim he didn’t do it. He refers to himself in moments as a “wretched” man capable of extreme violence. Uh, yeah, there was that time he bit off a piece of Holyfield’s ear.

Tyson made lots of green very fast and had no idea how to handle it. The film talks about athletes in other sports receiving guidance on how to manage the flood of income, but boxers don’t. Tyson spent his millions carelessly and ended up declaring bankruptcy in 2003.

“You never get over poverty,” he said. “I don’t care how much money you get or fame. You never forget that poverty hurts and leaves an everlasting effect on you.”

At times, it seemed like self-pity, but other times it ripped me open with empathy — like when he talked about being constantly bullied: “I stopped going to school because people was [sic] kicking my ass.”

When he told a story of getting in with kids who were robbing houses, Tyson cried. “They didn’t give me much money, but they bought me clothes.” My eyes welled up, too. When he spoke of the death of his 4-year-old daughter, Exodus, in 2009, OMG, I can’t even.

It’s clear that all three of these men were severely emotionally damaged by their miserable childhoods, which led to troubled adulthoods. “Nobody had anything,” said Hopkins’ trainer Naazim Richardson. “You couldn’t tease me about my mother being on welfare because your mother was on welfare.“

“The Real Deal,” aka Holyfield, is often referred to as the gentleman of the group; he’s described as a man with a strong sense of right and wrong. He was the youngest of nine kids. Neither of his parents could read, and he lived in poverty. He talked about how the people in his devastated community constantly threw their trash on the street, but his parents wanted him to have self-respect. People laughed at Holyfield and his family “because we picked that trash up.”

Hopkins, “The Executioner,” spent years in prison. By 13, he was mugging people and getting stabbed himself. At 17, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for nine felonies. He was introduced to boxing while incarcerated. When he got out, after serving five years, he converted to Islam and pursued a career in boxing.

These are complex stories that, at times, made me feel uncomfortable. I mean, plenty of people come out of devastating childhoods, and they don’t become violent criminals. But watching the reenactments of Hopkins’ childhood with voiceovers of him saying how poverty-stricken his family was, it’s impossible not to imagine what he was up against. With four sisters and three brothers, they had to divvy up one can of pork and beans for breakfast day after day after day. He said that once in a while his mom might throw some other things in, but it was still just pork and beans and not nearly enough of it.

This moving film would’ve benefitted from more fight scenes — think “Raging Bull” and “Cinderella Man.” It was also desperately in need of at least some levity. It is all unrelentingly sad — however, I must’ve liked it a lot because I watched it two more times.

“Champs” opens in theaters and becomes available on iTunes and VOD on Friday, March 13. Not rated. 91 minutes.

Watch the trailer:

Dorri Olds is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.

One Comment

Leave a Reply